January 2021: Speedy whistlers

Our arable fields can look very bare in winter, almost devoid of life. But look more closely, and listen. We have visitors from the north, flocks of them, sometimes noisy. Golden plovers, who arrived here in the autumn from the northern uplands where they breed. In summer plumage these are gorgeous birds, sporting gold-spangled upperparts and peat-black bellies, divided by a sinuous white band running down their sides. Nonetheless, they are surprisingly well camouflaged against the variegated colours of the moorland heather and you may only become aware of them from hearing a plaintive, fugitive whistle, almost lost in the wide and windy spaces. This was the sound Robbie Burns heard when he wrote of ‘the deep-toned plover gray, wild whistling on the hill.’ An old folk name for them was ‘rain bird’, but the two parts of the golden plover’s official scientific name are more oxymoronic in combination: Pluvialis apricaria ‘rain-bird, basking in the sun’. Given the changeable upland climate perhaps it was an attempt to connect the birds with both sun and showers.

In winter they migrate south to our fields and wetlands, where they congregate in large flocks, though they can still be hard to locate on the ground since they have now exchanged their contrasting summer colours for drab browns and greys that again give them perfect camouflage, only this time against the dun shades of the earth and mud on which they are feeding. If you carefully scan the fields up the Temple End Road, however, you will eventually make out the hunched profiles of some golden plovers on the ground. And when you have picked up a few, look again and you may find there are not just five, but fifty, or even a hundred or more, which gradually emerge from the background. They have a distinctive way of feeding – walking briskly head down for a few yards; a quick stab for worms or grubs; pausing, more upright and alert; then marching off again at different angle.

Every now and again, for no reason apparent to us, the flock may take off in a sudden dread. And now you hear their individual calls combined into a very distinctive whistling chorus that has the strange quality of being both muted and penetrating. These flocks swirl around in dense formations before the birds settle again back again on the ground in their invisibility cloaks. They are powerful flyers and, bizarrely, played a part in the creation of a publishing phenomenon. A spirited argument had broken out among the members of an Irish shooting party in 1951 about which British game bird was the fastest flyer – red grouse or golden plover? So Sir Hugh Beaver, who was one of the shooters but also happened to be head of the Guinness brewery, commissioned a volume to settle this and other such inconsequential facts – The Guinness Book of Records, which is now an annual best-seller. A golden gift to the publishers.

Jeremy Mynott, 12 January 2021

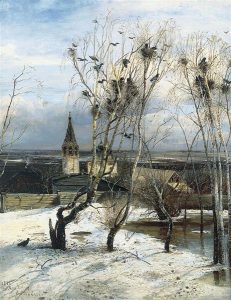

February 2021: The rooks return

‘The Rooks have returned’ is a famous painting by the 19th century Russian landscape artist, Aleksey Savrasov, who was much influenced by Suffolk’s own John Constable. The picture celebrates the return of rooks to their traditional nesting site in his village. Russian winters are so hard that rooks are summer migrants there, so for him this was a joyful sign of spring. Rooks are resident with us all year round, of course, but they are early breeders and are already busy rebuilding their rookeries. You can see them flying in with new twigs to repair nests shredded by winter storms, and also sometimes cheekily pinching some choice sticks from their neighbours’ constructions – hence our term ‘to rook’, meaning to fleece someone. But they are essentially sociable birds, foraging and roosting together, and nesting in these densely-packed colonies. The clamour from a rookery in the breeding season can be loud and raucous, to be sure, but the combined choral effect of all these individual conversations and altercations is powerfully evocative, even soothing. As soon as a BBC drama features an English churchyard scene you know they’ll soon be dubbing in a sound-track of rooks cawing in the tree-tops – a subliminal reassurance of an enduring rural idyll. Enduring except for the trees, that is. Rooks used to prefer mature elms, but they’ve gone; second choice was ash, also becoming endangered; so now most often sycamore, beech, chestnut and oak round here. Our nearest rookery, I think, is the one in the line of trees between Little Bradley church and Hall Farm stables.

Rooks and crows are often mistaken for each other, but the old country saying largely holds good, ‘A crow in a crowd is a rook and a rook on its own is a crow’. Shakespeare didn’t help this confusion with his line in Macbeth, ‘The crow makes wing to the rooky wood’. Scarecrows are misnomers, too, since it’s rooks they are meant to drive off the crops. In fact, this is doubly inappropriate since rooks feed mainly on grubs and insects, so serve to protect the crops, and that despite their scientific name of frugilegus ‘crop-picker’. Rooks and crows look quite different, anyway. Rooks have that whitish patch of bare skin round the base of the bill – visible from quite a distance; and their plumage seems one size too large for them, especially on the thighs, which look as if they are covered by baggy, feathered shorts. They walk differently, too. Crows stalk about rather menacingly, while rooks just waddle.

The collective term for rooks is a ‘parliament’. I used to think that too staid a word for their noisy, obstreperous gatherings. But the way things have gone recently in the world’s parliaments, I now think it may be unfair to rooks.

March 2021: Far away and long ago

There’s a lot of excitement about this Perseverance mission to Mars. The technology is amazing and the information we are getting back is remarkably detailed. For example, the night-time temperature there yesterday was a bracing -98F. They’ve equipped that extraordinary Rover vehicle to search for signs of past life. If they find any, it’s likely to be in the form of fossilised microbes about 3.5 billion years old. The mission is costing $2.7 billion and is thought a small price for satisfying the deep human urge to reach out and find life elsewhere in the universe.

I couldn’t help comparing that sum, however, with the current UK budget of £258 million for nature conservation and the protection of biodiversity. There is life on earth, right here and now, and it needs some help. Some of our own ancient inhabitants are in real trouble. Bees evolved in the Cretaceous period, some 120 million years ago, at about the same time as flowers, with which they have ever since formed a mutual support system. The bees pollinated the flowers, which competed for their attention with the huge variety of different colours, shapes and fragrances that the flowers evolved to lure them in. In turn, the flowers offered the bees pollen and nectar and the bees themselves diversified and adapted to take advantage of this bounty. We come into this biological equation too, since we depend on crops the bees have fertilised – in fact it has been estimated that the value of pollination for human food is more than £110 billion a year.

But bees are declining fast. They have lost important habitats of flower-rich meadows and have suffered terrible collateral damage from pesticides, herbicides and the other -cides, as well as from parasites. We’ve all read the headlines about this, but how much do we really know about this wonderful family of insects? Most people can recognise a bumble bee and a honey bee, but did you realise we have 24 different kinds of bumble bee in Britain and 270 other kinds of bee? Or that 250 of the latter are called ‘solitary bees’, which don’t live in hives or big colonies and have a huge range of life-styles, indicated by such intriguing names as miner, mason, leaf-cutter, wool-carder and sweat bees (yes, attracted by perspiration). Worldwide, there are over 20,000 different species of bees, more than all the birds and mammals put together, each occupying a different niche and enriching the planet in their own ways.

Well, you can see where my Easter parable is heading. Are we at risk of learning more about 3 billion-year old microbes on a dead and uninhabitable planet 140 million miles away than about the buzzing and blooming life that sustains our own live one and that lifts our hearts again every spring?

Jeremy Mynott

Stop Press. See this link for an important East Suffolk initiative. https://www.eastsuffolk.gov.uk/news/wildlife-to-benefit-from-more-wild-spaces/

Come on West Suffolk!

April 2021: Sounds of spring

All the talk is of a ‘return to normality’. Yes, I know people are longing for that but, as the old saying goes, we should be careful what we wish for. One of the compensations of lockdown has been that people have been exploring their immediate surroundings much more closely than ever before and seeing all sorts of things that were always there but unnoticed. Hearing them, too – for one of the revelations of the first lockdown was how transformative it was to be spared the noise pollution of air and road traffic and to hear all the natural sounds again with such clarity. The buzzing of bees, the gentle soughing of leaves, a babbling stream, and above all the chorus of spring birdsong – all balm to the ear. It felt like a new experience, but it’s also an ancient one. Here is the Greek poet Theocritus, celebrating the sounds of summer in the third century BC:

Over our heads many an aspen and elm stirred

And rustled, while nearby a sacred spring

Gurgled gently, welling up from a cave.

In the shady foliage of the trees the dusky

Cicadas were busy chirping, and some distant songster

Murmured from deep in the thorny thickets.

Lark and finch were singing, the turtle dove crooned,

And bees hummed and hovered, flitting hither and yon.

Well, that sounds pretty familiar, if you change cicadas to crickets and think back to the time when we did still have turtle doves and elms. But I worry about that ‘distant songster’ he mentions. As the traffic builds up again, I’ve noticed that the softer and higher-pitched ‘murmurings’ of birds like goldcrests, blue tits, coal tits and tree creepers are getting harder to pick out against the background din. And that isn’t just my ageing ears suffering what audiologists call the ‘cocktail party problem’ of picking out individual voices in a crowd. I seem to spend more time in the woods than at cocktail parties anyway, but the real problem is that now even the birds are now finding it increasingly difficult to hear each other. Research shows that they are having to sing louder to be heard in the modern world and that many of them are having to abandon otherwise suitable habitats near busy roads for just that reason. They sing their hearts out but never find a mate. I find that very sad. Think of a visual world that consisted only of loud colours. Think of an orchestra that only had trombones, cymbals and drums. So much of the beauty of both the landscape and the soundscape depends on variety, subtlety and harmony.

As for the desire to return to ‘normality’, whatever that is, we might bear in mind Oscar Wilde’s version of the old saying with which I started, ‘When the gods wish to punish us, they answer our prayers’.

Jeremy Mynott

10 April 2021

May 2021: Go wild

I’ve been keeping a log-book. Literally. I’ve been very restricted in my walking recently by a hip-problem (now fixed, I hope), but I found a mossy old log by the river I could just get to and rest on, completely out of sight. I’ve been sitting quietly on that, making notes on what comes by. It’s a quite different kind of nature-watching from the one I’m used to – striding out freely and actively exploring the world. But it turns out to have its own compensations when you adjust to it, which you have to do mentally as well as physically. Your world has shrunk to a radius of just a few yards, but it’s still teeming with life. And instead of pursuing nature you just have to be still and let it come to you. Which it does, surprisingly quickly.

After a few minutes, I hear a rustling very close by. A beetle? A mouse? No, it’s a wren, working its way busily through the undergrowth, picking up tiny insects invisible to my eye with deft little pecks and pounces. I don’t move a muscle, trying to look like an extension of my log. The wren’s nearly at my feet when it senses an unusual presence and flicks a little way off to continue its rummaging, but not before I get my best-ever view of its subtly variegated dead-leaf colours and the stiff little cocked tail. Now a moorhen paddles slowly by in the river, quite unaware of me, and a male blackcap sings from a branch – so close that its pure fluting song is almost too piercing. After an hour of immobility, I’m almost a woodland feature. A seven-spot ladybird lands on my hand, some wood ants investigate my boots, and the wren makes another pass, more boldly this time. And now a butterfly settles right next to me in a patch of sunlight – a male orange-tip. What a beauty! This is the first I’ve seen this year and it really does capture the spirit of spring with those sunshine orange flashes on its wings. Soon there will be lots of them on the wing searching out their favourite plants, garlic mustard and lady’s smock, both them just coming into flower now with perfect timing. The orange-tip’s Latin name is Anthocharis, ‘flower grace’ and the French call it L’aurore, ‘the dawn’, a nice suggestion of a new beginning.

Some people walk by just the other side of the river, another interesting species that doesn’t notice me, or very much else, I fancy. There’s a move to re-wild our landscapes, but I emerge from my immersion in nature feeling that we could all do with some rewilding ourselves. We’re part of nature too.

Jeremy Mynott

16 May 2021

June 2021: A local exotic

A neighbour reported an unusual bird on their lawn the other day. They wondered if it could be some exotic visitor from overseas. It was quite large, they said – the size of jackdaw but slimmer and very brilliantly coloured, flashing a bright yellow rump in a V-shape up the soft green back. And it sported a most striking head pattern with a black mask enclosing a white eye, topped off with a scarlet crown. It wouldn’t have looked out of place in a tropical jungle, but here it was hopping about on the grass in front of their house. When disturbed, it flew off in a bounding flight and appeared to clamp itself, as if magnetised, on to the trunk of a nearby willow.

Well, that was a very good description of what is certainly a charismatic bird, but not in this case an exotic one – it’s a common British resident, the green woodpecker. We naturally associate all our native woodpeckers with trees, as their name suggests, and they do indeed use their powerful dagger bills to excavate nest holes in tree-trunks, probe the bark for grubs and drum on hollow branches to advertise their presence both to rivals and potential mates. But the green woodpecker has also developed this further habit of using its formidable drilling equipment to dig into ant colonies in our lawns and lick up the inhabitants with their specially adapted tongues. The artist Leonardo da Vinci, who observed everything with insatiable curiosity, was fascinated by woodpecker tongues – why were they so long, he asked, and how were they housed in the woodpecker’s head when they were retracted? The answer was later revealed by dissection and is illustrated in this little diagram of a skeleton: the tongue is literally wrapped around the brain and its elastic movements are controlled by specially adapted bony cartilages.

In spring, the male green woodpecker has a very distinctive territorial call, a descending peal of (usually seven) loud ‘laughing’ notes that gave the bird its old country name ‘yaffle’. Another folk name was ‘rain bird’. It was widely believed that the yaffle’s call presaged rain, which would bring out the insects on which the bird feeds. An easy prediction to make in Britain, perhaps, when it is always about to rain anyway, but quite false. Possibly it derived from an even older, more primitive belief in the woodpecker as the ‘thunder bird’, who summons up the rain with his resounding drum-roll and wears the red badge of lightning on his crest.

Anyway, no need to invoke foreign exotica with such wonders close to home.

Jeremy Mynott

7 June 2021

July 2021: Benign neglect

Sometimes the best form of conservation action is inaction. The poet Gerard Manley Hopkins visited Loch Lomond in 1918 and afterwards wrote these lines, entranced by the wonders of its wild and untouched nature:

What would the world be, once bereft

Of wet and of wildness? Let them be left,

O let them be left, wildness and wet;

Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet.

Further south, it sometimes feels as though we are waging a war on wildness. We transfer the house-proud virtues of keeping our homes clean and tidy on to the countryside itself, as if it was a kind of extension of our living rooms. Take the case of roadside verges. There’s no need to keep these shorn like carpets, as many landowners and local councils do, bereft of the teeming life that depends on them. We have over 300,000 miles of rural roadside verges in this country, so that’s a major natural resource, equivalent in size to about half of the whole area of flowering meadows and grasslands we still have left (and we’ve lost a terrifying 97% of those to agricultural or urban development in the last 75 years). Our verges support over 700 species of flowers overall and that’s nearly half our total flora. Never mind that you might think some of them weeds if they were in your front garden. What’s a weed but a flower in the wrong place? I walked a length of our local verges the other day and they were ablaze with vetches, trefoils, scabious, knapweed, thistles, ox-eye daisies, meadowsweet, clovers and cranesbill. And all these flowers in turn support legions of butterflies, moths, bees and other insects. The bird’s foot trefoil, for example, feeds some 130 species of invertebrates, and it’s estimated that just a mile of flower-rich verge can produce 20kg of nectar-sugar, enough to sustain several million pollinators like these.

Verges do need to be cut periodically, or else the weight of dying vegetation would eventually overwhelm them and stifle next year’s growth, but the time to do this is at the end of the summer, ideally August/September or even later, when the seeds will have been shed. That way you maximise biodiversity. But there’s no need to go for suburban neatness, which amounts to mass ecocide. The old ‘Best-kept Village’ awards used to be judged partly on ‘tidiness’, but we know better now. The name ‘verge’ comes from the Latin virga, the staff of official responsibility, indicating the extent of the holder’s power, and our civic responsibilities now extend to saving our declining wildlife. The Little Thurlow Parish Council is giving a good lead on this locally by establishing some of our verges as ‘Nature Reserves’. Hurrah for the activists on the Parish Council!

O let them be left, wildness and wet;

Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet.

Jeremy Mynott

10 July 2020

August 2021: Domestic wildlife

I’m on the Suffolk coast now, where our ‘garden’ has been very fully re-wilded after we’ve been absent for almost a year through lockdown. I’ve written before about how we should encourage and welcome more rewilding: that is, habitats for more wildlife – more animals and birds, more butterflies and moths, frogs and toads, lizards, and wild flowers. And here they all are, in great abundance, which is wonderful, especially the clouds of butterflies on the buddleia: red admirals, peacocks, tortoiseshells and even a local speciality, the grayling. But after a year, not surprisingly, the house has also been re-wilded to some degree, and this has been more of a test of my resolution (and my wife’s, I should add), since there is a limit to the number of visitors we can entertain. In fact, most of the spiders were very decent about it and largely withdrew on our arrival, while the ones that stayed on have been useful in catching flies and other less welcome insects. One of these residents is a particularly interesting species, the so-called daddy-longlegs spider. This isn’t to be confused with the real daddy longlegs, which is a cranefly and not a spider at all. We have some of those here too, but they are quite different. They have two wings and six legs (not eight like a spider) and they’re the flying insects that skitter about harmlessly in late summer with improbably long, and easily detachable, dangling legs. When they get into the house – drawn to the lights, presumably – they usually give up the ghost pretty quickly, drowned in wash-basins and toilets or frizzled inside lampshades.

The daddy-longlegs spiders are permanent house residents, though. They were originally a sub-tropical species, which humans then carried with them all around the world. They were first recorded from cellars in southern Britain in 1864 (hence the old name ‘cellar spiders’), but have now moved upstairs and spread throughout the country, largely due to climate change, and you’ve almost certainly got some in your own house. The scientific name is Pholcus phalangoides, which literally means ‘bandy-legged’, and they use their long spindly legs like fingers to probe and ‘sense’ their surroundings. They are generally very slow-moving creatures, crawling across ceilings or walls to rob the prey trapped in the webs of other spiders or even catching their fellow spiders by surprise and so usefully clearing the house of those. When disturbed themselves they have the dramatic habit of vibrating rapidly to create a sort of visual blur, which makes it more difficult for a potential predator to locate them precisely and know where to stab or peck. I much enjoy watching this whirling display and I also welcome them for catching a few gnats and mosquitoes in their own, almost invisible, webs. By the way, they also have eight eyes, so they are probably watching you, too.

Jeremy Mynott

15 August 2021

September 2021: The humbler creation

There’s plenty of public support for protecting charismatic species of wildlife like golden eagles, beavers, red squirrels, swallowtail butterflies and oak trees – even domestic alpacas, just recently. But what about ‘the humbler creation’, as the hymnist called them, of insects, beetles, and worms that actually make the world go around? Especially worms. Worms have traditionally been regarded as the lowest form of life. The word itself comes from the Latin vermes from which we get ‘vermin’, and to call someone a ‘worm’ suggests they are beneath contempt. But as any farmer will tell you worms are critical to the health of the land. They devour and recycle dead vegetation, and act as tiny ploughmen to aerate, drain and fertilise the earth. The richer the soil the more earthworms there will be in it, so those worm-casts on your neatly cut lawn are more like compliments than disfigurements. And it’s been estimated that in an acre of good pasture there may be a greater weight of worms under the soil than there is of livestock above it.

All the great naturalists in history have praised worms. Aristotle called them ‘the intestines of the soil’, while Charles Darwin studied them for over 40 years and observed, ‘It may be doubted whether there are any other animals which have played so important a part in the history of the world’. Quite some testimonial! My favourite worm quote, however, comes from the peerless Gilbert White, curate of a small village in Hampshire, whose Natural History of Selborne (1789) is said to be the fourth most published book in the English language (after the Bible, Shakespeare and John Bunyan). White is the spiritual father of all today’s nature diarists (including this one) and Selborne is the record of his daily observations. He lived in the same house all his life and rarely left his tiny parish, but found riches enough in attending closely to the lives of all its creatures, great and small. Here he is extolling the worm and making a very modern point about the interconnectedness of all life:

The most insignificant insects and reptiles are of much more consequence, and have more influence in the economy of Nature, than the incurious are aware of; and are mighty in their effect… Earthworms, though in appearance a small and despicable link in the chain of nature, yet, if lost, would make a lamentable chasm. For, to say nothing of half the birds, and some quadrupeds, which are almost entirely supported by them, worms seem to be the great promoters of vegetation, which would proceed but lamely without them.

In some cultures we become part of this chain too by eating worms – the Maori traditionally regarded them as a great delicacy; and in most other cultures we willingly submit to the reverse process on our deaths …

Jeremy Mynott

9 September 2021

October 2021: Back to school?

How much do young people know about nature? Do they ever look up from their phones for long enough to actually see anything? We may be about to find out since there are plans to introduce a new GCSE in Natural History and the Cambridge University Exams Board is right now working out a curriculum. As a taster, they sent round these sample questions below.

1.Grampy pig, hardback and curly bug are all common names for a:

(a) earwig; (b) woodlouse; (c) centipede?

2.Muntjac deer are the size of a:

(a) domestic cat; (b) large dog; (c) cow?

3.Is a slow worm a:

(a) worm; (b) snake; (c) lizard?

4.Horseshoe, pipistrelle and Bechstein are all UK species of:

(a) bat; (b) deer; (c) orchid?

5.Which of the following is a visitor to the UK (ie, not resident):

(a) little tern; (b) song thrush; (c) wren?

6.Dead man’s finger (Xylaria polymorpha) is common in woodlands. Is it a:

(a) fruit; (b) fungus; (c) flowering plant?

7.A glow-worm is:

(a) a beetle that can chemically produce light; (b) a worm with a glowing tail; (c)

a beetle that rubs its wings together to produce sparks?

- You are walking in the countryside and find a deep 15cm conical hole with foul-smelling liquid poo in the bottom. Is it:

(a) a rabbit toilet; (b) a badger latrine; (c) fox poo?

9. How many eggs do long-tailed tits lay:

(a) 5-8; (b) 8-15; (c) 16-20?

10.Which of the following species is native to the UK?

(a) sycamore tree; (b) brown hare; (c) wildcat

11.How do mussels attach to rocks:

(a) with strong, sticky threads; (b) clamp on with their muscles; (c) small tube feet?

12.The turtle dove has declined by over 90% since the 1970s. The main reason is:

(a) hunting by humans; (b) predation from other animals; (c) loss of habitat?

13.Is a brown argus:

(a) a butterfly; (b) a moth; (c) a dragonfly?

14.How fast does a gannet hit the surface of the sea when diving for fish:

(a) 20mph; (b) 60mph; (c) 100mph?

15.How many different species of beetle are there in the UK:

(a) 150; (b) 1,300; (c) 4,200?

I reckon some of these are quite difficult, so top of the class if you got twelve or more right. But if it was under five, now’s your chance to add another qualification to your cv. Never too late. Answers below (don’t cheat!).

Jeremy Mynott

November 2021: Let there be darkness

I’m writing this on 1 November, when we have just changed the clocks and plunged deep into darkness until 27 March next year I wish we could just stay with Summer Time myself, as the EU plans to do and as (little-known fact) we actually did in Britain experimentally from 1968-71; but then the Scottish farmers weighed in and said it was unfair to cows to change their milking-times. Why even tell the cows if they have a problem with it, I wondered at the time, but maybe I was missing a point about circadian rhythms. These are the automatic systems that constitute our 24-hour body-clocks and they manage all kinds of bodily functions like sleep patterns, mental alertness, cell regeneration and brain-wave activity. They are triggered by changes from light to dark and are called ‘circadian’ from the Latin circa diem (‘about a day’). All animals and plants have them – they control the precise timing of things like hibernation, reproduction and migration, and you can watch some flowers literally closing down for the night as dusk falls.

We used to do that too, but in the last hundred years or so we have found two ways of scrambling these control mechanisms. First, we can travel rapidly through time zones, delaying the onset of night by five hours, for example, if we fly to New York – hence jet-lag. Secondly, we are the only species that now lives a good proportion of its life in artificial light, which we had never evolved to do in the long millennia before electricity arrived in every home – hence insomnia.

We’re also increasingly inflicting this insomnia on the natural world, through light pollution in our big cities. It wasn’t a nightingale that sang in Berkeley Square, it was almost certainly a robin, confused by the street lights into thinking that dawn had arrived. We read of baby turtles in Florida heading back up the beach to certain death instead of following the light of the horizon down to the sea. One study in the US estimated that some five million birds might die each year from becoming disoriented in migration and colliding with tall buildings. And probably billions of insects perish in the glare of lights to which they are irresistibly attracted, so in turn depriving insectivorous songbirds of their usual food supply and further depleting their numbers too. As for glow-worms and fireflies, forget it: the ingenious courtship signals developed over millions of years of evolution are completely lost against the backdrop of skyglow.

We humans need to be able to see the stars, too, if only to realise our own insignificance. But just look at this satellite picture of London by night. Soon everywhere will be over-lit … except Little Thurlow, I hope.

Jeremy Mynott

10 November 2021